Why Art Matters: From Scribbles on Walls to Cultural Revolution

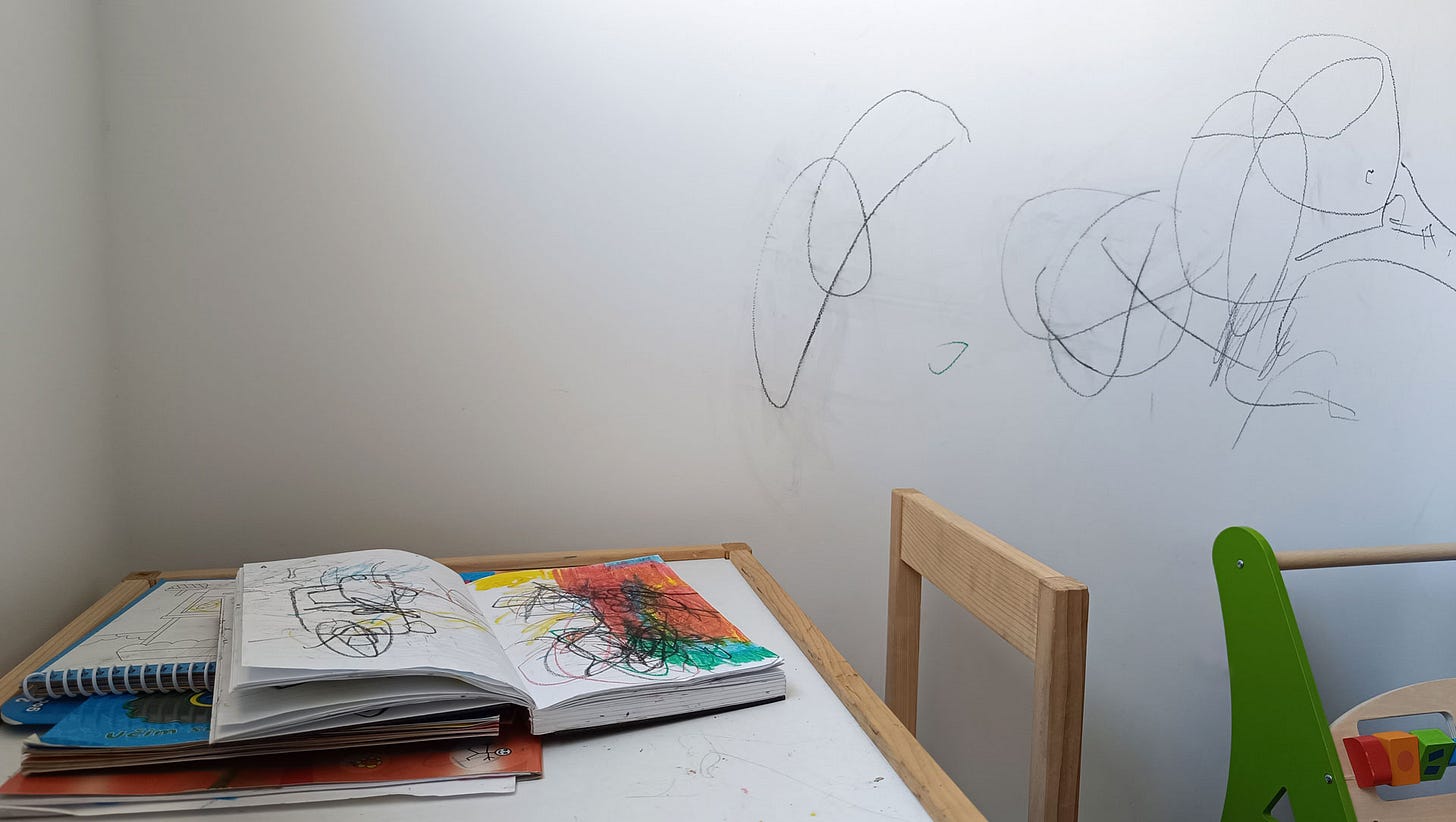

A view from my son's bedroom: notebooks full of experimental marks and unauthorized wall drawings that somehow capture the essential human need to create

The evidence sits right there on my dining table, scattered across my son's bedroom walls, and honestly, in every corner of human civilization: we are compelled to make marks, to create, to express something that can't be captured any other way.

Those chaotic scribbles in his notebook—overlapping circles, bold color patches, lines that go nowhere and everywhere—aren't just random marks. They're proof of something fundamental about human nature that we've somehow convinced ourselves is optional, decorative, or worse, elitist.

Art isn't a luxury. It's how we think.

The Cognitive Revolution Hidden in Plain Sight

Every innovation, every breakthrough, every solution to humanity's challenges began with the same creative thinking process that produces art. The cave paintings at Lascaux weren't just pretty pictures—they were our ancestors figuring out visual communication, symbolic thinking, and shared meaning-making. Without that foundation, we wouldn't have developed writing, mathematics, or the conceptual frameworks that built civilization.

When my son covers that wall with unauthorized drawing (much to our mixed feelings about it), he's participating in the same cognitive process that led to every human advancement: the ability to imagine something that doesn't yet exist and figure out how to make it real.

This is why dismissing art as "nice to have" is fundamentally misunderstanding what art actually is. It's creative problem-solving made visible. It's the training ground for the kind of thinking that invents new technologies, solves complex social problems, and pushes human understanding forward.

The Translation Problem

But here's where things get complicated. Art's importance is often invisible precisely because it works so well. We see the end result—a painting, a sculpture, an installation—without understanding the cognitive heavy lifting that created it or the cultural conversations it's participating in.

This is where curators become essential. As Robert Storr, former curator of the Venice Biennale, explained in Sarah Thornton's "Seven Days in the Art World":

"Curators bring things to your attention that would not have otherwise come to your attention. Moreover, they bring works to you in a way that makes some kind of vivid sense."

Think about that for a moment. In our information-saturated world, the ability to bring meaningful things to people's attention and make them make sense is perhaps one of the most valuable skills imaginable. Curators aren't just arranging objects in rooms—they're creating frameworks for understanding.

When Storr describes his approach to group exhibitions, he notes:

"It's not about masterpiece displays; it's not about choosing the top forty. It's about creating some kind of texture out of the variety of art—against which individual works can mean more."

This is sophisticated cultural work. It's about creating contexts where individual pieces of creative thinking can be understood, compared, and built upon. It's making the invisible visible.

Democratizing Understanding

The art world has a reputation for exclusivity, but that misses the point entirely. The problem isn't that art is inherently elitist—it's that we've created unnecessary barriers to understanding it. When we explain contemporary art using academic jargon instead of clear language, when we assume prior knowledge instead of providing context, when we treat appreciation as a privilege instead of a skill anyone can develop, we're failing at our most important job.

This is precisely why DLightful Services exists. Our mission isn't to make art more accessible by dumbing it down—it's to make art more accessible by explaining it better. We believe that anyone can understand and appreciate art when it's presented with clarity, context, and genuine enthusiasm rather than pretension.

Every time we help an artist articulate their vision more clearly, or support a gallery in communicating why their exhibitions matter, or translate complex art theory into practical insights, we're working toward the same goal: making the importance of art visible and understandable to broader audiences.

The Bigger Picture

Those scribbles on my son's wall remind me that the urge to create, to express, to problem-solve visually is deeply human. But somewhere between childhood and adulthood, many people become convinced that art is something that happens to other people, in special places, following rules they don't understand.

That's the real tragedy. Not that some people don't "get" art, but that we've organized our cultural institutions and conversations in ways that make people feel excluded from something that should be as natural as breathing.

As Storr puts it:

"Great art is essentially work that has proven inexhaustible in terms of the value it gives to those who pay attention to it."

The key phrase there is "those who pay attention to it." Not those who have special training, or expensive education, or insider knowledge. Those who pay attention.

Our job—whether we're curators, gallerists, artists, or simply people who care about culture—is to create more opportunities for people to pay attention, and to make that attention as rewarding as possible.

Because when that happens, when someone really sees and understands a piece of art for the first time, something clicks. They recognize the creative thinking process they've been using their whole lives, just applied with more intention and skill. They see the connection between artistic innovation and every other kind of innovation. They understand that art isn't separate from practical life—it's the engine that makes practical life possible.

That recognition changes everything. And it starts with taking those scribbles seriously.

What moments of creative expression have you witnessed that reminded you why art matters? How do we bridge the gap between artistic innovation and public understanding?